Thoughts on "A Glimpse of Heaven"

So I came across this very interesting chapter from a very interesting character — Jack Edmonds. And it was a completely random encounter. I believe it was a Tuesday or Wednesday afternoon, a couple days before the big Spring Festival holidays. I was pretty wrapped up with the projects on my plate. One thousand percent certain that I was not in the mood to start something new because my mind was already out the window. So I decided to touch up my coding skills a little by learning a trick or two.

I did an exercise on dynamic programming — which is a super cool algorithm technique, by the way, if you've never heard of it — and then I asked AI on a scale of 1 to 10 how advanced dynamic programming is. To my disappointment, the AI basically said it's just a medium-hard algo. (Disappointment because I thought I'd skied down a black diamond but realized it was only a blue trail.) So I said, okay, if you think that was medium-hard then shoot me with some hard-hard algorithms. One of them, the blossom algorithm, caught my eye — probably because it's got a cool name.

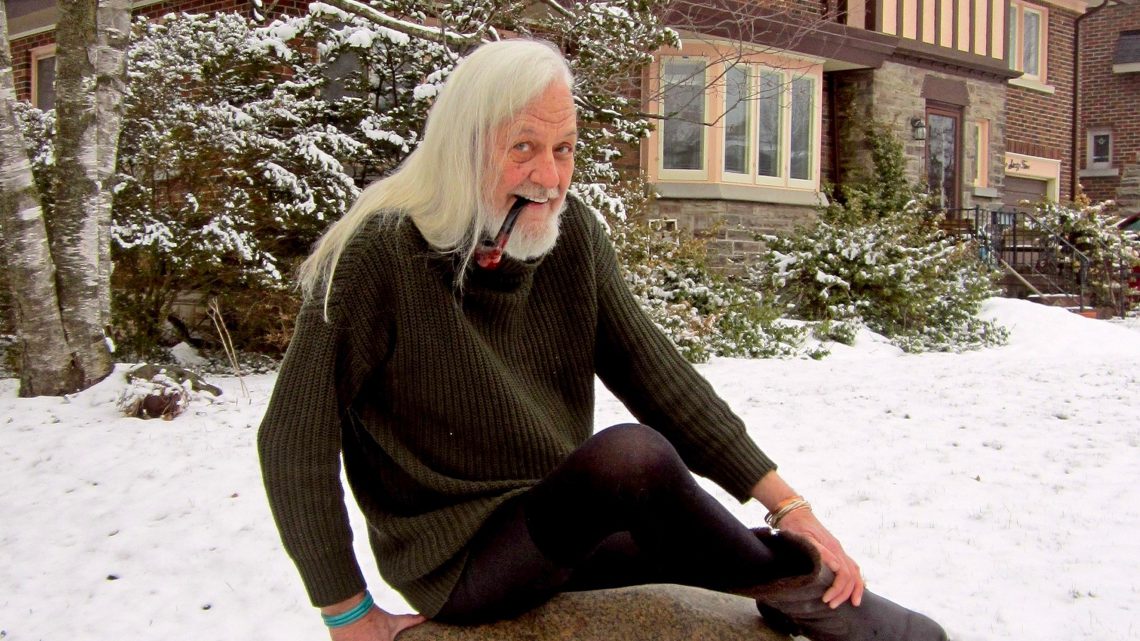

Then I looked up the blossom algorithm, and holy cow — I swear Jack Edmonds, the person who invented it, is like Gandalf in real life. They should have invited him to play Gandalf, and he wouldn't even need makeup. I mean, just look at the photo: that hair, that beard, that smile, that pipe. Tell me he doesn't look like an archmage who possesses all the magic and wisdom.

That led me to this chapter, "A Glimpse of Heaven," which is an interview of him at Oberwolfach in 1991. Oberwolfach is where they give out the John von Neumann Prize, which is basically the Nobel Prize for computer science. That said, Sir Edmonds is really a mathematician, and he won the prize in 1985, not 1991.

The interview is a bit long, and maybe not the easiest thing to follow because he frequently references very technical mathematical lingo — but man, he is an interesting character. Prideful, brilliant, a gentleman, a rebel by heart. I'll just share the paragraphs I highlighted while reading and drop a thought or two on each.

The Gentleman Student

"I don't survive on ability, I survive on taste."

Edmonds talks about flunking measure theory, then flunking complex analysis from his favorite teacher Horváth — not because he didn't care, but because he cared too much in the wrong way. He loved the lectures, loved the arm-waving and the big ideas, but couldn't translate them into exam answers. So he took the courses again. And again. Different professors, different versions. He calls himself a "gentleman student."

I really resonate with both parts. There were a few classes I took that I genuinely enjoyed — Money and Banking was one, and I also really liked the astronomy class. I was the most active student in class, went to all the office hours, aced the homework, and frequently helped others with theirs. Yet I'd just choke during exams and end up with suboptimal grades. A gentleman student — what a nice way to put it.

And yeah, I also took an analysis course. Real analysis. (There are two types: real analysis and complex analysis, the latter being what Edmonds mentions.) That course is just hard. Thank you, Sir Edmonds, for confirming that analysis is hard, even for a brilliant mind like you. My teaching faculty were fantastic, and the parts I did get I thought were beautiful. But yeah — I didn't understand it sufficiently, and yeah, I deserved that B/B+.

Ideas vs. Technical Achievements

"Mathematicians don't present ideas, they only present technical achievements. That is one thing. And that is a damned shame."

I totally agree with him. I'm not really in a position to comment on mathematicians, being merely a graduate student who took some advanced math. That said, it does seem like the "good" mathematicians these days are the ones who can put together hundreds of pages of equations — and there are probably no more than three people who actually care to read or understand what they're saying. Has mathematics evolved so far that no PhD student could graduate with a five-page thesis of pure good ideas, no technicality show-offs? I don't know — maybe you could get away with five pages if the idea is that good.

And if you apply this more broadly, you find the same pattern everywhere. Maybe people spend too much time — and get rewarded too much — for putting together the most beautiful deck or email, or writing the most lines of code showing off unnecessary encapsulations. Substance over presentation. Ideas over technical flexing.

The Word "Algorithm"

Before you read the next part, take a guess: when was the word "algorithm" first invented?

Edmonds makes a fascinating observation. Hilbert, in 1900, was asking whether an algorithm exists for certain problems — but he didn't even know what an algorithm is. Gödel didn't know. Church didn't know. It took thirty-five years to formalize the concept. Yet Euclid had presented the Euclidean algorithm thousands of years earlier. Cardano presented algorithms for solving cubic equations. Mankind had been presenting algorithms for millennia. The Arabs invented the word. And yet somehow, all of mathematics' greatest minds were using algorithms without having any formal definition of one.

People had been inventing algorithms for thousands of years — and only figured out what they actually were in the 1900s. Wild.

The Von Neumann Award

"It reaffirms that what we are talking about here is an underachiever who had a chip on his shoulder."

Edmonds got emotional about winning the Von Neumann Prize. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to him. But he's also quick to say he doesn't actually like Von Neumann — whom he felt took credit for contributions that should've belonged to Turing. (Didn't Nobel also get criticized for taking credit for other people's work? See the commonality?)

"An underachiever who had a chip on his shoulder" — what a sentence.

Turing and the Mathematicians

"Mathematicians have got to defend what they know in terms of technicalities... You don't get brownie points except for technical accomplishments in this game. Mathematicians don't like philosophers."

Similar thread as above. In my field of trading, I sometimes explore random ideas — studies that don't monetize, at least not directly. If work can't be turned into a "strategy," it's considered useless a lot of the time. Kind of like me reading this interview and writing down thoughts on it.

A Glimpse of Heaven

"Here is a good algorithm, here is a solved integer program... this was a real sermon. Here is a solved integer program. It was my first glimpse of heaven."

This is when he made the huge breakthrough. The room was full of legends — Gomory, Dantzig, Tutte, Fulkerson, Hoffman, Bruck. He gave what he calls a grand philosophical speech, and it all came together. A glimpse of heaven. Happy for the guy.

Learn It Well

"Learn linear programming, learn it well."

Edmonds talks about how he didn't know the simplex method, didn't know the Ford-Fulkerson algorithms. He was kind of faking it among these giants, trying to hide what he didn't know. And then Alan Hoffman, over morning coffee, told him simply: learn linear programming, learn it well.

Yes sir. I will learn linear programming. I will learn it well.

Hiding the Square Root of Two

Edmonds references the old story about Pythagoras wanting to hide the square root of two — and connects it to his own desire to hide certain technical gaps from the OR seniors he was trying to impress.

You know who else would want to hide the square root of two?

Shove Your PhD

"I laid this on them and they agreed to disagree, and I said: 'Shove your PhD!'"

Edmonds dropped out of school multiple times and I believe never got a PhD. He was deeply critical of many academic traditions, and as a result, not everyone liked him. He felt the PhD program was a medieval system where "academic priests protect their positions," watching students drift away as failures. He told the professors exactly what he thought. Classic rebel move.

Seeing Problems From Where You Stand

Edmonds talks about his collaboration with Ray Fulkerson. Fulkerson's gift was being able to see almost every theorem under the sun as a network flow problem. Edmonds, meanwhile, was trying to see everything as a matroid problem.

I think people tend to see problems from their own ground. I'm still young, so I can't say for sure, but what you work on in your early years really shapes how you see problems. That means it's valuable to talk to different people from different backgrounds — even the ones you think you'll disagree with. You'll often find useful new perspectives.

Ready to Be Einstein

"As far as I am concerned, that theory that I worked out in the sixties is at least as important as what Einstein did, and I am ready to be Einstein."

If you read this paragraph out of context, you'd think — who the hell is this arrogant person, comparing himself to the great Einstein? But reading the full interview, you understand. Edmonds originally had many of the great ideas but couldn't always formulate them into formal algorithms or theorems. He wasn't always welcomed by the academic community. He did most of his foundational work in the 1960s but only got recognized in the late 1980s. He shared ideas with people who later published them as their own.

I read a hurt pride here. It's not arrogance — it's the frustration of someone who knew what he had, knew its worth, and had to wait decades for the world to agree.

He is still alive and 91 years old. Wish him good health.